Brunch: An Examination of Its Controversial, Yummy History

Though its origins are muddled, this made-for-weekends meal is a late-morning party.

Jul 07, 2025

The debate over the origins of brunch reads like an international whodunit. Credit for the portmanteau of "breakfast" and "lunch" goes to British author Guy Beringer, who wrote an 1895 essay titled “Brunch: A Plea" for the periodical Hunter's Weekly. Beringer's idea was to create an alternative to ornate post-church dinners and touched on many aspects of brunch that prevail today, from allowing “carousers" to sleep in on Sundays to being a “sociable and inciting" gathering.

Where did brunch come from?

But hold on. Was brunch actually invented a few decades earlier by a New Orleans chef, a German immigrant who employed French-Creole cooking techniques? At her restaurant, Begue's in the mid-19th century, Elizabeth Kettenring Begue served only one meal per day, what the Times-Picayune described as “a sumptuous, multi-course, multi-hour affair that began at 11 a.m. and which she called 'second breakfast.'"

Or is that still too Western an attribution, considering that the brunchlike dim sum, with its parade of small plates, dates back to 10th-century China? The “dim sum" brunch has even become a subgenre in itself, with many restaurants offering variations on the concept in and out of Chinatowns.

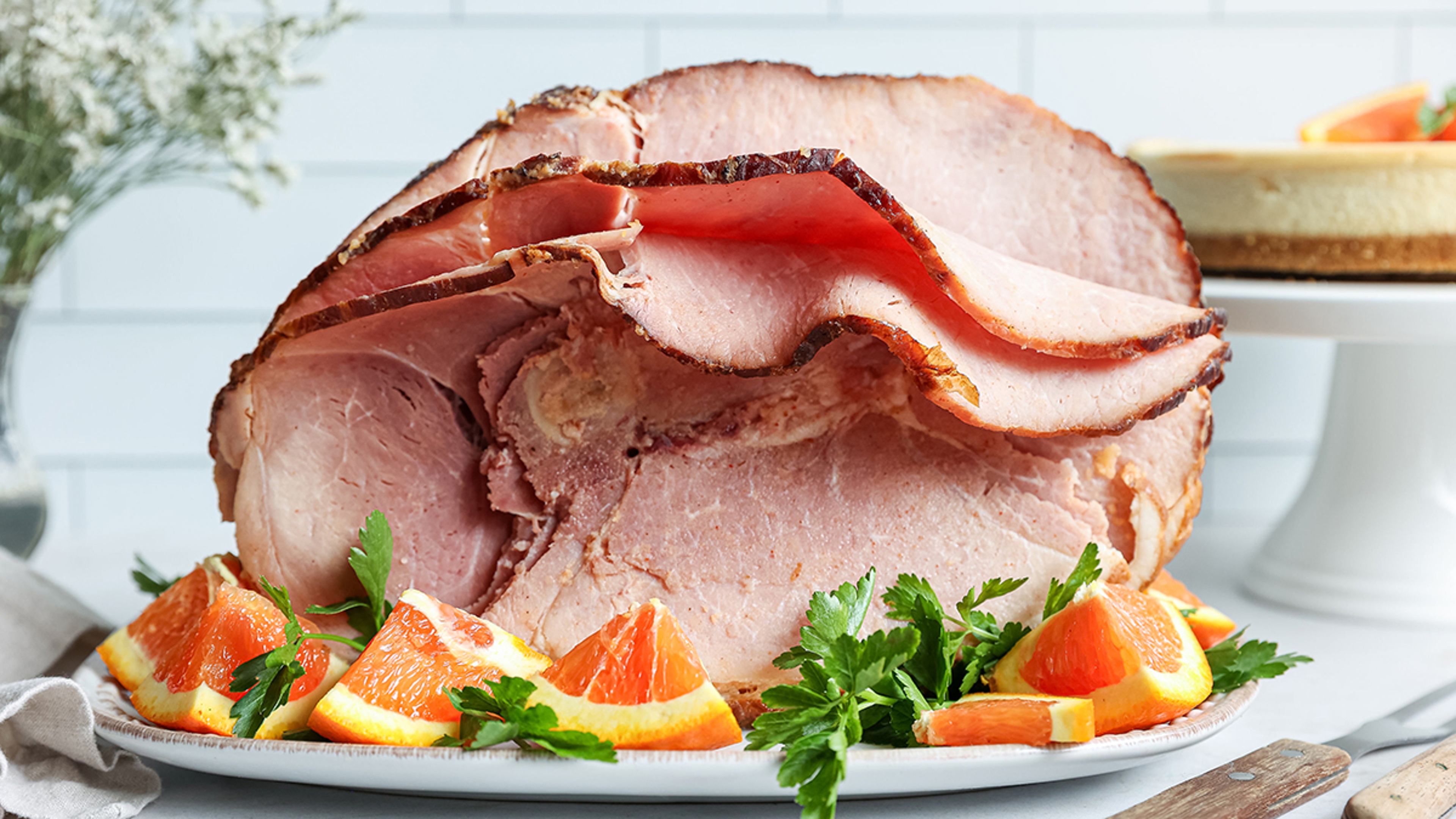

Whatever its origins, brunch today is a well-established weekend alternative to breakfast or lunch. Usually enjoyed on Sundays, it is a meal that has spawned signature savory and sweet dishes and drinks, from eggs Benedict on English muffins to French toast with fruit to, of course, the famed brunch cocktails, the bloody mary and the mimosa. At restaurants and at home, families come together for Mother's Day and Father's Day brunches or to celebrate religious holidays such as Easter and Hanukkah for festive brunches.

READ MORE: Where in the World Did the Bloody Mary Come From?

So how did brunch become so ingrained in our culture, the only meal to insinuate itself among breakfast, lunch, and dinner?

In the United States, at least, a confluence of early- and mid-20th-century factors led to a rise in the popularity of going out to brunch. These include celebrities supposedly enjoying late-morning breakfast while traveling, influencing fans to do the same; housewives taking jobs during World War II while their husbands fought overseas, leading women to favor a morning off from cooking on weekends; and the appearance of luxurious breakfast buffets at hotels.

According to Sarabeth Levine, founder of New York City's best-known brunch institution, Sarabeth's, the hotel buffets pervaded through much of the 20th century. That was until restaurants like hers came along and hit upon the idea of combining sweet and savory breakfast items with lunchtime favorites like sandwiches and burgers — and, of course, alcohol (the aforementioned bloody marys, mimosas, and even wine pairings).

“I truly believe that Sarabeth's put brunch out there," Levine says. “I don't think there was much of anything with brunch, other than at the hotels."

The first location of Sarabeth's opened in 1983. It featured Levine's housemade jams and other sweet items, as well as popular egg dishes like the Goldilocks Scramble, made with smoked salmon and cream cheese. Levine introduced eggs Benedict a few years later and began expanding Sarabeth's to other parts of the city. In a testament to brunch's popularity today, Sarabeth's now has 17 locations in New York City, Florida, Dubai, Japan, and Taiwan.

As a brunch expert, Levine explains the enduring attraction of this popular meal like this: “Brunch is kind of like a morning party. I don't know how else to describe it."

Brunch in pop culture

Many restaurants have benefited from this late-morning meal. Friends gather for Sunday brunch in cities, creating scenes of young people, often looking haggard from their Saturday night festivities, standing around on sidewalks, waiting for their party's name to be called. The phenomenon even inspired a 2012 episode of the cult comedy show Portlandia, in which dozens of disgruntled 20-somethings wait in a queue to vie for a table at a hot brunch spot.

Brunch has had its detractors, though, including singer Mariah Carey, who facetiously argued on Twitter that a better bridge between meals would be “linner." In a Simpsons episode, brunch was described as: "It's not quite breakfast, it's not quite lunch, but it comes with a slice of cantaloupe at the end. You don't get completely what you would at breakfast, but you get a good meal." The late Anthony Bourdain called brunch a "devil's bargain" because, he said, it's profitable for restaurants, but chefs hate making it; he and others have excoriated brunch as a ploy for chefs to use up leftover ingredients on the weekends. Even famed chef and cookbook author James Beard reportedly griped, "If I'm going to have sausage and eggs, I want them in the morning. I think I'd banish brunch and ask people for late breakfast, between 11:30 and 12, or I'd ask them for lunch at 1.''

Of course, brunch these days is about more than sausage and eggs. Restaurants and home cooks have elevated the meal to an art form, creating bloody marys festooned with small burgers, shrimp, and pickled vegetables, turning waffles and pancakes into platforms for fresh, seasonal fruits and flavored syrups, and showcasing eggs in the form of omelets and scrambles.

No matter where brunch actually started, there's no denying it's delicious, and it's clearly here to stay.

.svg?q=70&width=384&auto=webp)